At 63 years old, Wareham’s David Paling decided to embark on a second career as an oyster farmer. He shared his story with us in the current print issue of South Coast Almanac and we’re reprinting it here. Settle in and read his story (and join us for a boat ride to his shellfish grant on July 20th — details below)…

On good days being an oyster farmer can feel like you’ve got the best job in the world. When cool weather and low tides sync, and your boat is running well, and the tasks that day are not back-breaking, and all around you have hundreds of thousands of happy oysters suspended in their floating bags silently gobbling up planktonic food and growing like crazy, it is easy to reach the level of happiness that is elation. The miracle of farm raising Crassostrea virginica — Eastern oysters — can do this. Bliss comes in many forms: an hour or two wading in quiescent water and finding nothing wrong with gear, nor any evidence of human or natural predation; the freedom of being the master of your own liquid domain, driven by tide and weather rather than artificial schedules imposed by more traditional occupations; the thrill of seeing your crop — fingernail sized when you bought them from a hatchery — achieve the three-inch length, deep-cupped status required by today’s market forces; the wonder of nature all around you with cobalt skies and shimmering sun overhead and teal water below giving life to the likes of so many species. The list is simply too long to capture. In times like these, the work doesn’t seem like work, and you feel lucky to be amidst these marvels, a part of the ecosystemic, global spin.

But there are bad days as well, and it becomes quite clear that oyster farming is not easy money and physically not something that anyone can get up from their chair and do. To wit: Steve Patterson and myself, general partners and owners of Crooked River Shellfish Farm, have accidentally dumped our oysters on the substrate by miscalculating the mesh size of our containing bags. We’ve had closure flaps fail, spilling yet more of our young spat along the shallow bottom. We’ve bounced our boat — the ‘All In’ — off the docks. We’ve gone home bleeding from contact with razor-sharp barnacles and oyster shell edges. There have been other low points. The first day we found dead oysters, natural victims of the expected mortality rate dealing with them, I got a whiff for the first time of this necrotic slop and it smelled as bad as, no worse than, a dead oyster. The constant repetitions of hoisting some 183,000 oysters in and out of the boat for culling purposes has escalated degeneration and my arthritis has me hurting from topgallant mast to stern. And once, when replacing the drain plug after emptying the boat of sea water at full throttle, I threw myself, my wife and oldest daughter Carly all out of the ‘All In’ when it took a violent right turn the moment I let go of the wheel.

So why at the age of sixty-three did I come to co-establish the Crooked River Shellfish Farm in Wareham on seven acres of ocean leased to me? The idea of doing aquaculture had occurred to me over the years, but not in any clear, distinct way. Rather it was a fuzzy, furtive notion that crept into mind during the most trying moments throughout a career in education. I grew up in Wareham and spent a good deal of time on its 57-miles of shoreline as a recreational shellfish digger. I observed from a distance the fascinating work of a couple of long-time quahog and oyster farmers. Shellfish, unlike growing teens, didn’t talk back and I occasionally fantasized about reigning over my own mollusk estate.

Want to meet the Crooked River Oyster farmers? Join us for a field trip to their oyster farm on July 20th aboard the roomy and comfortable Miss Chris boat, from Onset Pier from 4 to 6 pm. $49 per person ($44 for South Coast Almanac readers) includes the boat ride and a half dozen Crooked River Oysters per person, along with conversation and stories from David and some of his crew. Email [email protected] to reserve your spot.

But I never acted on these impulses, eventually reached retirement and settled into a peaceful existence, until one day an old friend named Steve Patterson, whom I hadn’t seen in many years, asked me, “Would you be interested in trying to get a shellfish grant here in town and starting an oyster and quahog farm with me?” I had met Steve some 40 years ago, and we had bonded through common fishing and shellfishing experiences we had growing up, I in Wareham and he in Wellfleet. Since that experience, however, we had gone our own ways and had crossed paths just a couple of times in many years. He said he lived in Sandwich now. He worked at Roger Williams University where he held the title of Field Manager. His work on the water for the school’s aquaculture department there involved an effort to restore the wild oyster population in the state of Rhode Island. But his dream was to turn his attention full time to being an independent oyster farmer.

I felt driven to do this, and from that point forward I considered myself all in (the name of the Carolina Skiff we’d buy later was borne of this moment). The general partnership we’d form was mutually beneficial. Residency was required to obtain a shellfish grant in Wareham, so Steve needed me to realize his dream (the exposed coastline in Sandwich did not lend well toward aquaculture). I had a keen familiarity with the local waters. I also had a team at my disposal. My wife, Sue, was drawn in immediately to the idea of oyster farming. My daughters Carly and Kelley and Carly’s husband Ben also wanted in on the action.

I felt driven to do this, and from that point forward I considered myself all in (the name of the Carolina Skiff we’d buy later was borne of this moment). The general partnership we’d form was mutually beneficial. Residency was required to obtain a shellfish grant in Wareham, so Steve needed me to realize his dream (the exposed coastline in Sandwich did not lend well toward aquaculture). I had a keen familiarity with the local waters. I also had a team at my disposal. My wife, Sue, was drawn in immediately to the idea of oyster farming. My daughters Carly and Kelley and Carly’s husband Ben also wanted in on the action.

And I needed Steve. I’d never been a grower, whereas he had worked in several capacities that connected to oysters and aquaculture. He held a Master’s degree in environmental education and had been a science teacher at a high school where he established an aquarium and aquaculture club with his students. He also served as Operations Manager for a Massachusetts shellfish hatchery. These experiences culminated in the position he held at Rogers Williams University. There he spent about ten years propagating oysters and establishing reefs in an attempt to restore the wild population that had been wiped out by parasitic diseases.

Want to meet the Crooked River Oyster farmers? Join us for a field trip to their oyster farm on July 20th aboard the Miss Chris boat, from Onset Pier from 4 to 6 pm. $49 per person ($44 for South Coast Almanac readers) includes the boat ride and a half dozen Crooked River Oysters per person, along with conversation and stories from David Paling and some of his crew. Email [email protected] to reserve your spot. Steve Patterson has a mania for oysters higher than a moon tide

Oysters are Steve’s passion, and he will talk about them until you tell him to stop. The people affiliated with the university’s oyster restoration project referred to him, in fact, as “Oyster Steve.” You might spot him in town doing errands. He’d be the one wearing waders and a belt with a silver buckle in the shape of an oyster. Steve Patterson has a mania for oysters higher than a moon tide.

It took about one full year before we had secured all the necessary approvals. Wareham Harbormaster Garry Buckminster was receptive to more aquaculture enterprise in town. With his support, the Board of Selectmen gave approval to my application. Then, the Division of Marine Fisheries approved after scuba divers surveyed the area for seaweed (attractive to other marine life), and existing sets of shellfish. Since the site was devoid of seaweed and there were very few shellfish (an abundance of shellfish could have supported the commercial industry), we also got a green light here. Then the local Conservation Commission, resident abutters, and area Wampanoag Indians had opportunity to oppose. The Conservation Commission application process also involved the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, which noted that Diamond-backed Terrapin turtles, a threatened species, used this area as habitat. It was not a deal breaker, however. Approval was given for our quahog and oyster farm. Finally, the Army Corps of Engineers gave their thumbs-up and we were done. The tsunami of bureaucracy had been overcome.

It took about one full year before we had secured all the necessary approvals. Wareham Harbormaster Garry Buckminster was receptive to more aquaculture enterprise in town. With his support, the Board of Selectmen gave approval to my application. Then, the Division of Marine Fisheries approved after scuba divers surveyed the area for seaweed (attractive to other marine life), and existing sets of shellfish. Since the site was devoid of seaweed and there were very few shellfish (an abundance of shellfish could have supported the commercial industry), we also got a green light here. Then the local Conservation Commission, resident abutters, and area Wampanoag Indians had opportunity to oppose. The Conservation Commission application process also involved the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, which noted that Diamond-backed Terrapin turtles, a threatened species, used this area as habitat. It was not a deal breaker, however. Approval was given for our quahog and oyster farm. Finally, the Army Corps of Engineers gave their thumbs-up and we were done. The tsunami of bureaucracy had been overcome.

Of the 500 million oysters sold in America each year, 30 million of these come out of Massachusetts. We were on our way toward becoming part of this growth industry. We bought stainless steel hog rings, coils of rope, plastic mesh oyster bags, plastic floats — gear necessary to establish a floating bag system — and got to work. We made some 100 of the smallest size mesh bags we would need to hold our spat, and 200 of a bigger size mesh into which they would be re-located when they grew long enough. We formed the bags on a homemade wooden jig and hog-ringed them together over beer and music in my garage. Steve bought a used, 16’ Carolina Skiff, a flat-bottomed working vessel with no seats from an acquaintance in Rhode Island and hauled it back home.

We prepared our site in March with a series of spiral anchors used to keep all our floating gear in place. Horizontal ropes were attached to these anchors on which we’d clip our floating bags. “They will grow like Chia Pets,” Steve noted. “The southwestern fetch here is conducive to oyster growth.”

A floating bag system allowed our gear to move through the water column with the tide, keeping it in constant contact with the food the oysters exist on. This system also allowed us to take advantage of wave action that naturally tumbled the oysters. This tumbling served to strengthen the shells and deepen the cups.

A floating bag system allowed our gear to move through the water column with the tide, keeping it in constant contact with the food the oysters exist on. This system also allowed us to take advantage of wave action that naturally tumbled the oysters. This tumbling served to strengthen the shells and deepen the cups.

When we put our first 66,000 tiny seed in the water in the spring of 2017, our understanding was that it would take at least 18 months for them to reach market size. Eight months later we were able to sell several thousand of these before things got too cold to work in December. We purchased 50,000 more in May and another 67,000 in August, bringing our grand total to 183,000 oysters. Among these were a number of triploids, oysters that by design had three sets of chromosomes resulting in infertility. The triploid purchase was part of Steve’s master plan.

“Triploids don’t spend their time on sexual matters,” he explained. “Since they don’t waste time producing sperm and eggs they grow bigger and faster than other oysters that have two sets of chromosomes. They should be fat and marketable all year round.” Why our oysters grew so fast is part science and part mystery. Oyster farming, like real estate, can be successful because of location. Temperature, salinity, water cleanliness, depth and substrate can vary according to where you are.

The Crooked River Shellfish Farm is located in an area of Wareham still undeveloped, rendering septic system and agricultural runoff at least partially moot. From a certain vantage point on our grant there is nothing on the horizon but the open Atlantic Ocean (swim this way and the first land mass you may come upon are the Azores) which creates a colossal flushing effect when tides come and go, keeping the spot pristine and nutrient rich.

Our farm is also within an elbow formed by a wooded shoreline and sand bar, theoretically causing phytoplankton to pause here. This floating buffet gets presented to 183,000 growing babies two times each day with the rise and fall of the tide. This scientific positing notwithstanding, Sue thinks our oysters grow fast because she talks to them. “Hello my little darlings,” she says, hovering over the first floating bag of the day.

Wild Eastern oysters are bivalve mollusks that, before disease practically wiped out populations of them all along the east coast, grew in prolific numbers. Parasitic diseases took dramatic tolls on them in the 1980s, as did an uptick in ocean acidification levels and warming temperatures. In response to this suppression the norm became farm-raised oysters. Nearly all you eat from any supermarket or restaurant these days come from someone’s individual efforts. And more oyster farms are being established each year. The Wareham Selectmen, in fact, recently gave approval to yet another fledgling operation, which will bring the total number of oyster farms in this town to seven. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries statewide data shows 70 new farms established in 2016.

Wild Eastern oysters are bivalve mollusks that, before disease practically wiped out populations of them all along the east coast, grew in prolific numbers. Parasitic diseases took dramatic tolls on them in the 1980s, as did an uptick in ocean acidification levels and warming temperatures. In response to this suppression the norm became farm-raised oysters. Nearly all you eat from any supermarket or restaurant these days come from someone’s individual efforts. And more oyster farms are being established each year. The Wareham Selectmen, in fact, recently gave approval to yet another fledgling operation, which will bring the total number of oyster farms in this town to seven. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries statewide data shows 70 new farms established in 2016.

While growing your own oysters presents several unique challenges, it can be lucrative. The fact that you can buy an oyster seed for more or less a nickel and sell the same oyster several months later for 60 cents is a significant monetary lure.

As filter feeders, a single oyster can open its shell and pump some fifty-gallons of water per day in its quest for food. When hundreds of thousands of oysters exist in a concentrated area, a body of water may effectively be kept clean. They take in damaging nitrogen (too much nitrogen results in a loss of critical habitat for marine species) from the water and it forms part of their shells. This filtered water is beneficial toward the growth of sea grass, and sea grass represents breeding ground for other species. This quality is a substantial reason why there have been efforts made to restore wild populations and why many coastal towns have been receptive to allowing oyster farms to exist.

The appeal with oysters is that they have terroir, tasting something of their point of origin. When we first sampled our product we thought Crooked River Shellfish Farm oysters had the characteristic taste of fresh water from the Tihonet River mixing with salt water from the Wareham River about a mile away, a pleasant convergence of not too much, nor too little brine. They were, we thought, an oceanic version of the perfect Manhattan.

Crooked River Shellfish Farm oysters had the characteristic taste of fresh water from the Tihonet River mixing with salt water from the Wareham River about a mile away, a pleasant convergence of not too much, nor too little brine. They were, we thought, an oceanic version of the perfect Manhattan.

Consumers of raw oysters should proceed with caution, however, because oysters can hold toxins. And Vibrio — bacterium found in brackish saltwater — can cause gastrointestinal upset and in extreme, rare cases even result in death. You should therefore know where the oysters you eat come from. Oyster farmers who are cognizant of and conscientious with food safety regulations (keeping harvested oysters on ice, for example) can help minimize these ugly possibilities.

A typical summer workday on the Crooked River Shellfish Farm starts at low tide with a pleasant ten-minute boat ride from a marina in town where we lease a shallow water slip in their low rent district. The ‘All In’ is a mutt among show dogs at this marina but we are not alone. There are a few other vessels designed for labor parked there as well, their hulls bearing the pride of barnacles and smelling of hard work. The majority of our commute occurs in a no-wake zone so we chug along deliberately.

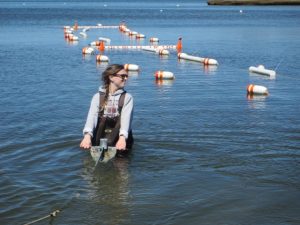

Once on the farm we dress in waders or wet suits and go about the business of flipping, flushing, culling and, in Sue’s case, conversing. We crank music from a waterproof stereo Carly bought me for Father’s Day, and cull as many oysters as possible until the tide comes in and it becomes difficult to walk the floating bags back to their position on our hawser lines. A wise old oysterman once noted that farm raising oysters was all about moving them. You’ve got to constantly shuffle your crop around. It’s hands-on work, done by all-hands-on-deck. And the more of this you do, the more successful you will be.

We devise names for oysters based upon size: BFJ’s are big, fat and juicy. Undoable Doubles are oysters that have permanently attached themselves to one another. Graduates are those oysters that get relayed to larger size mesh bags. Runts have not yet realized their growth spurts.

We devise names for oysters based upon size: BFJ’s are big, fat and juicy. Undoable Doubles are oysters that have permanently attached themselves to one another. Graduates are those oysters that get relayed to larger size mesh bags. Runts have not yet realized their growth spurts.

The work is rewarding, exhausting and for me triggers the desire to drink cold beer. Our oyster season runs roughly from March through December, a course parallel to the feeding cycle of the species (they feed almost continuously except in the winter). The oyster farmers who own and operate the Crooked River Shellfish Farm will go mostly dormant in the winter along with their 183,000 clients. Only the grizzliest of veterans work in January and February.

For example, we were busy in November and December, harvesting a few thousand market sized oysters and bringing them to a wholesaler in tagged bags of 100.

Simultaneously we condensed the smaller ones into less bags, removed the floats from each bag and sunk them to the bottom in 3-4 feet of water for the winter. You had to look down now to find them, but still, there were oysters everywhere. It was mid-December when we finished, taking the ‘All In’ out and getting her winterized. As dependable as she was this inaugural season, we learned she’d need $1,400 in repairs before we would launch again this spring.

We’re talking about expansion, increasing our total number of oysters on the farm. We might put out some 50,000 quahogs as well. We’re anxious to see the results of our triploids. Steve’s working on a tumbling device that we’ll add to our oyster management repertoire. At any rate, I’d really like to stay aboard the ‘All In’ all the time next year. And grow a lot of oysters.

-David Paling

Did you like this story? Want more like it? Sign up to become a subscriber of our quarterly print publication. Our early summer issue is popping with great content (a Tiverton farmhouse that flirts with industrial style, the sport of Azorean whaleboating and the people behind it, behind-the-scenes with local dairy and oyster farmers, a fashion shoot in Padanaram Harbor, and lots more). If you want a copy delivered to your door with things you won’t see online, subscribe right here!

Or just help us spread the word about South Coast Almanac by sharing this post with your friends on facebook, twitter or by email.

Can you tell Steve we found an oyster bag washed up on our beach if he would like to retrieve. Have photo

Hi Mike, I’m sorry….we don’t have Steve’s current contact info!