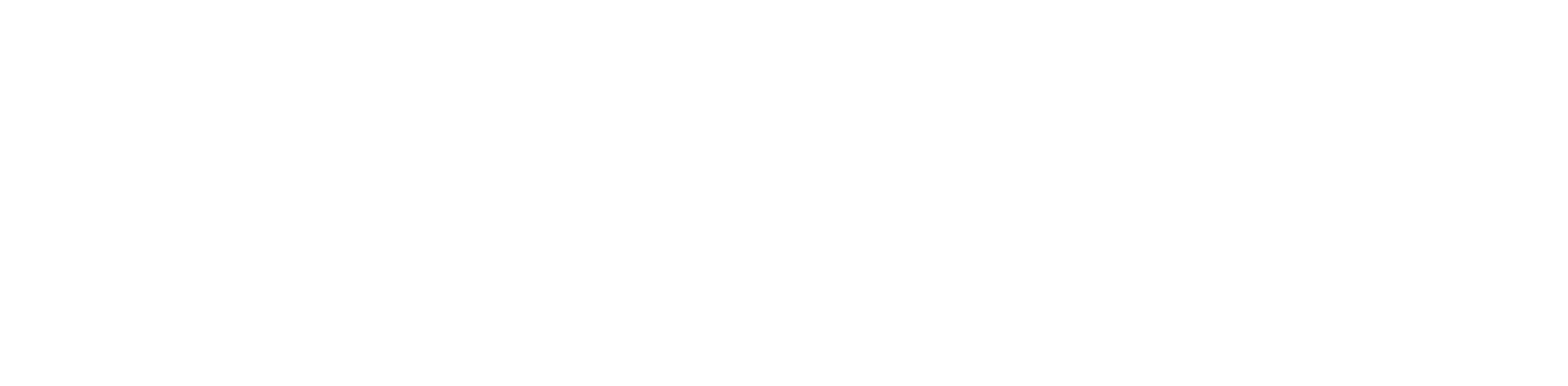

It’s just before dawn at Clark’s Cove and a group of women of all ages are beginning to gather. It’s going to be a beautifully clear July day once the sun rises so we are all dressed simply in t-shirts and sneakers. But for the fingerless gloves (to protect our hands from monster oars), we look like we’re on our way to a gym class. Lisa and Lara begin prepping one of the long colorful boats. Its inside is painted a cheerful bubblegum pink, reflecting the mood, at least for me.

It’s just before dawn at Clark’s Cove and a group of women of all ages are beginning to gather. It’s going to be a beautifully clear July day once the sun rises so we are all dressed simply in t-shirts and sneakers. But for the fingerless gloves (to protect our hands from monster oars), we look like we’re on our way to a gym class. Lisa and Lara begin prepping one of the long colorful boats. Its inside is painted a cheerful bubblegum pink, reflecting the mood, at least for me.

“We’re down one girl,” Lisa Lemieux, the boat steerer says.

Lara Harrington hands me a 50-pound oar that looks to be over 15 feet long, “Looks like you’re rowing.” And just like that I’m introduced firsthand to the sport of whaleboat rowing.

Other cities have rivers with crew teams sculling on fiberglass shells. The South Coast has colorful wooden whaleboats, nearly 40 feet long and elegantly tapered at the ends, that troll the harbors around New Bedford and Fairhaven with thrilling vistas of the Hurricane Dike, the working waterfront, and a skyline marked with gothic towers, old mills and church spires. These vessels were used continuously in the whaling industry in the 1800s.

Today, the boats are filled with men and women enjoying them recreationally. Some have been rowing (or sailing) for years — or some, like me, may have just joined the fun.

Today, the boats are filled with men and women enjoying them recreationally. Some have been rowing (or sailing) for years — or some, like me, may have just joined the fun.

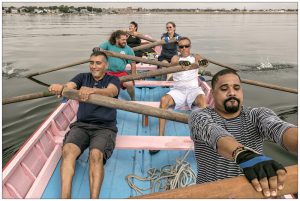

New Bedford is home to three of only 63 authentic Azorean whaleboats in the world (and the only ones in

the United States). Handcrafted by a master wooden boat builder, they are so beautiful that you might

expect them to be museum pieces. One of them — the Bela Vista — is in fact co-owned by the New Bedford Whaling Museum. But it’s a living, breathing exhibit: simply look out at the harbor to see them in use by passionate teams of rowers or sailors. Then, take a moment to imagine them as the vehicles created to capture 60-foot sperm whales, operated entirely by manpower.

In the Azores, the hunt for sperm whales began when the vigia (the lookout) alerted the town that he had spotted a whale. The whalers would quickly run to their boats to give chase to the giant creatures, some of which could reach lengths of 70 feet. Seven brave and strong souls made up a boat: one steered, five rowed and one was ready with the harpoon. It’s hard to fathom that this is how it was done just 50 years ago.

“…usually in the clear light approaching sunrise, a rocket is fired and within a few minutes, amidst shouts of ‘Baleia, baleia!’, the whalemen are running down to the boat slip or manhandling the boats from their sheds.”— Robert C. Clark, Open Boat Whaling in the Azores

How New Bedford acquired three Azorean whaleboats is the story of a strong local woman who cherished her Portuguese heritage. Dr. Mary Vermette wanted to recognize the many Azorean whalers who had emigrated to this region. She was instrumental in bringing the Bela Vista to New Bedford in September 1997. She founded the Azorean Maritime Heritage Society (AMHS) later that year. In a 1999 Standard-Times interview, she said, “the whaleboats are a bridge between here and the Azores; something physical of our past that we can see, that shows the presence of the Azorean people here.”

How New Bedford acquired three Azorean whaleboats is the story of a strong local woman who cherished her Portuguese heritage. Dr. Mary Vermette wanted to recognize the many Azorean whalers who had emigrated to this region. She was instrumental in bringing the Bela Vista to New Bedford in September 1997. She founded the Azorean Maritime Heritage Society (AMHS) later that year. In a 1999 Standard-Times interview, she said, “the whaleboats are a bridge between here and the Azores; something physical of our past that we can see, that shows the presence of the Azorean people here.”

Two more boats were built in New Bedford soon after, using traditional techniques by the same master boat builder who had built the Bela Vista in the Azores. Now, 157 South Coast residents are members of the AMHS, more than a third of them are active rowers/sailors. More than two hundred others make up the other local whaleboat rowing clubs (the Buzzards Bay Rowing Club and Whaling City Rowing). Just look out at the harbors to begin to realize the legacy created by Dr. Vermette, who passed away in 2003.

Curious newcomers are encouraged to attend an open row (unlike the other clubs, the AMHS also offers open sails). If they’re like Lara Harrington, the boats become a passionate part of their lives. Lara came to it as a curious South End neighbor, who was fascinated watching the AMHS boats in Clark’s Cove. When her friends’ parents asked if she wanted to give it a try and form a team with some younger women, “I jumped at the chance,” she says. “We collected a group of our friends and rowed together for two years.” She is poetic when she talks about whaleboat rowing, “It’s a conversation with the water, with the boat, the oars, the people and the wind. It’s not something you learn, it’s something you grasp. It’s building a relationship with all of these elements.”

Curious newcomers are encouraged to attend an open row (unlike the other clubs, the AMHS also offers open sails). If they’re like Lara Harrington, the boats become a passionate part of their lives. Lara came to it as a curious South End neighbor, who was fascinated watching the AMHS boats in Clark’s Cove. When her friends’ parents asked if she wanted to give it a try and form a team with some younger women, “I jumped at the chance,” she says. “We collected a group of our friends and rowed together for two years.” She is poetic when she talks about whaleboat rowing, “It’s a conversation with the water, with the boat, the oars, the people and the wind. It’s not something you learn, it’s something you grasp. It’s building a relationship with all of these elements.”

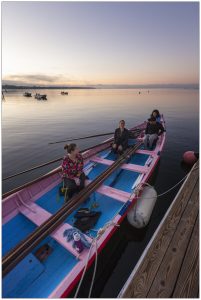

Newbies are welcomed aboard and generously taught the ropes. It’s not what you think, not the kind of rowing you’re used to from your traditional dinghy. The steersman calls out, “Ready all!” You get into the starting position: reach forward, arms out straight. “Pull together!” Lean disarmingly far back, then pull the oar straight back to your chest. Don’t dip the oar too far into the water. Keep the same beat as the others. When you’re new to this, you’re quietly focused even as conversation ricochets around you, because you’re trying to keep to the boat’s rhythm. It feels good to be part of something with a strong rhythm.

It feels good until you find yourself sitting on the bottom of the boat — it’s called crabbing and it happens when the oar gets stuck in the water and the force you’ve been putting into rowing transfers its energy into pushing you back, sometime right into the bottom of the boat. The others in the boat have all done the same, so no need to feel embarrassed. It’s just the oars and the water hazing you.

It feels good until you find yourself sitting on the bottom of the boat — it’s called crabbing and it happens when the oar gets stuck in the water and the force you’ve been putting into rowing transfers its energy into pushing you back, sometime right into the bottom of the boat. The others in the boat have all done the same, so no need to feel embarrassed. It’s just the oars and the water hazing you.

Over in Fairhaven on Friday afternoons (also Sunday and Wednesday mornings), the Crabalots are pushing off for their weekly row. The average age in their boat is over 70. Vi Taylor says “the kid in the boat” is 63. But they’re in far better shape than most 30-year-olds I know. When I ask them how intense the rowing is, the answer, like so many things, is that it depends on the day. Some days they train hard. Some days are more leisurely. Someone says, “This ride? In terms of calories? 2 glasses of wine.”

There’s an easy camaraderie that envelops the boat as it pushes away from the dock and hits the open water. The women chat companionably while rowing and then, under the direction of the boat steerer, they buckle down and burn a trail through the water. It’s like a friendly social hour peppered with bouts of focused exertion where the only voice is the steerer: Pull! Pull! Pull!

There’s an easy camaraderie that envelops the boat as it pushes away from the dock and hits the open water. The women chat companionably while rowing and then, under the direction of the boat steerer, they buckle down and burn a trail through the water. It’s like a friendly social hour peppered with bouts of focused exertion where the only voice is the steerer: Pull! Pull! Pull!

Traditional crew is known for its toughness, its ability to handle pain. These are the guys that David Halberstam chronicled in The Amateurs — purists who welcome pain and suffering for the love of the sport. Frankly, they’ve got nothing on whaleboat enthusiasts. While the AMHS stores its boats from November to May to preserve them from the elements, the Buzzards Bay Rowing Club and Whaling City Row offer year-round rowing. Gerry Roche leads the Engine Room team, a group of men in their 40s and 50s who row every Sunday morning at 8 am all year long. Roche says he likes winter rows even more than summer rows: “it’s quieter, there’s no boat traffic, the water is smooth and you warm up pretty quickly.” When Gerry’s team returns to the dock at the end of their row, they fill the next team in on the day’s idiosyncrasies: the wind, the currents, any sea life they may have encountered.

Year-round rowing means having a front row seat to some amazing late afternoon sunsets, early moonrises and to a special hardy camaraderie. The Whaling City Rowing Club (WCRC) boasts a team who has been rowing together for nearly 20 years. For the last 15 years, the Gray Buzzards have made a monthly long trek out to Butler Flats Lighthouse — six miles back and forth — in all sorts of weather. WCRC President Mark Hurley says, “two or three years ago, the harbors were getting close to freezing. The Gray Buzzards brought axes with them so they could break through the ice if they had to. Two days later, the harbor froze over for two weeks.”

Year-round rowing means having a front row seat to some amazing late afternoon sunsets, early moonrises and to a special hardy camaraderie. The Whaling City Rowing Club (WCRC) boasts a team who has been rowing together for nearly 20 years. For the last 15 years, the Gray Buzzards have made a monthly long trek out to Butler Flats Lighthouse — six miles back and forth — in all sorts of weather. WCRC President Mark Hurley says, “two or three years ago, the harbors were getting close to freezing. The Gray Buzzards brought axes with them so they could break through the ice if they had to. Two days later, the harbor froze over for two weeks.”

For many, whaleboat rowing is an opportunity to get outside and enjoy others’ company, to get some exercise and celebrate the outdoors while nurturing an activity deeply rooted in culture and history. For others, it’s a competitive international sport. These locals enter the International Azorean Whaleboat Regatta as the USA team on the world stage every other year, where they are very competitive. In 2017, they took second in rowing and sailing, in both the men’s and women’s divisions. This July [2019], they’ll travel to the Azores for the competition (the Regatta alternates locations between the Azores and New Bedford).

For many, whaleboat rowing is an opportunity to get outside and enjoy others’ company, to get some exercise and celebrate the outdoors while nurturing an activity deeply rooted in culture and history. For others, it’s a competitive international sport. These locals enter the International Azorean Whaleboat Regatta as the USA team on the world stage every other year, where they are very competitive. In 2017, they took second in rowing and sailing, in both the men’s and women’s divisions. This July [2019], they’ll travel to the Azores for the competition (the Regatta alternates locations between the Azores and New Bedford).

At the end of our row, the AMHS team skillfully approaches the dock, careful not to scrape against the side. They store the boats, the ropes, the oars and oarlocks, their focused attention in these chores revealing their reverence for the colorful wooden boats. When everything is finished, the women chat about an upcoming weekend social. Someone asks Dartmouth’s Lucy Amaral if she’s bringing her famous bacalhau to the social. Someone else asks if anyone wants to grab breakfast.

At the end of our row, the AMHS team skillfully approaches the dock, careful not to scrape against the side. They store the boats, the ropes, the oars and oarlocks, their focused attention in these chores revealing their reverence for the colorful wooden boats. When everything is finished, the women chat about an upcoming weekend social. Someone asks Dartmouth’s Lucy Amaral if she’s bringing her famous bacalhau to the social. Someone else asks if anyone wants to grab breakfast.

It’s not yet 7 am and they’ve just been part of something that feels a little magical. “It’s a team of people that understand each other,” says Lara Harrington. “You can feel the boat when your stroke is on point with everyone else’s.”

What a way to start the day.

Photos by John Robson

A version of this article appeared in our early summer 2019 print issue. Want to support stories likes this and see more of John Robson’s photographs in all their glory? Subscribe to the magazine and we’ll arrive quarterly in your mailbox with stories and photographs reflecting back the beauty and character of the South Coast! Subscribe right here for $19.99 a year.

A version of this article appeared in our early summer 2019 print issue. Want to support stories likes this and see more of John Robson’s photographs in all their glory? Subscribe to the magazine and we’ll arrive quarterly in your mailbox with stories and photographs reflecting back the beauty and character of the South Coast! Subscribe right here for $19.99 a year.