Westport resident Alan Poole shares his history of studying the beloved osprey, advocating for its survival and witnessing its resurgence on the South Coast. Reprinted from our Early Summer 2023 issue.

Story by Alan F. Poole. Photos by Alan F. Poole, Craig Gibson, James & Carole Mahaney & Kristopher Rowe

IT’S A SPLENDID MAY MORNING on a wide-open expanse of Westport River salt marsh, hints of green grasses starting to sprout from the warming mud and a dazzle of Buzzards Bay blue visible through a cut in the nearby beach dunes.

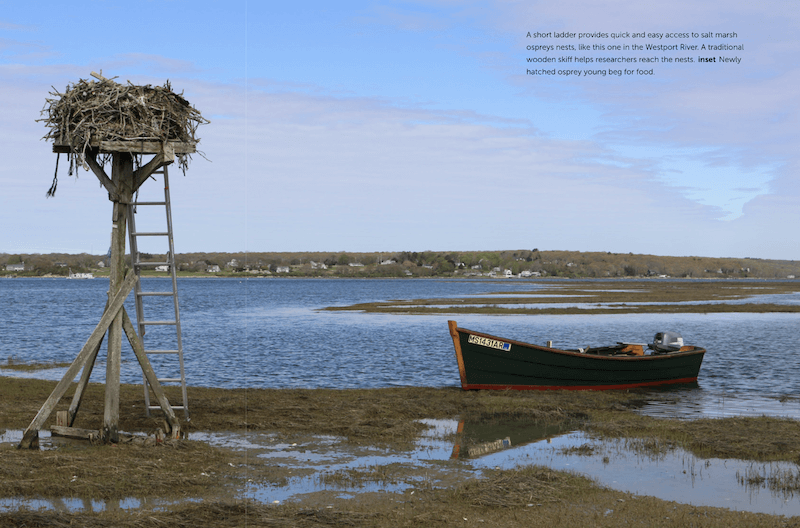

I’m on foot, a short aluminum ladder tucked under my arm. Strangers might wonder, but my riverside neighbors know what I’m up to. It’s osprey hatching season, and these wild expansive Westport marshes are dotted with big conspicuous nests, each a circular cluster of sticks, seaweed, and grasses atop five- to 10-foot poles.

Hence the ladder.

I lean mine against the first nest I come to, the parent birds circling warily overhead and calling in alarm. I climb to look over the nest rim.

My reward is instantaneous and heart-warming. Two tiny hatchlings, each covered in buff-colored down, are trying to stand but keep collapsing onto each other, like a tumble of newborn puppies. Heads wobbling in the sun and beaks open, begging with faint chirping calls, those hatchlings have just one purpose in life right now: getting bites of fresh fish (the only thing ospreys eat) from their parents as often as possible.

Climbing down, and walking quickly away to let the parents return to their nest, a few thoughts spring to mind. First, although I see this happen every year, I still find it mind boggling that these frail creatures, hardly bigger than my thumb, will—in just three months’ time—be transformed into robust, fully-fledged ospreys, capable of soaring on afternoon breezes and of snatching feisty striped bass and bluefish from the surface of our summer bays, before heading off alone in early fall on a 3,000-mile journey to winter along the shores of an Amazonian river. But I also think of the history here. Buzzards Bay was likely named for its nesting ospreys, the birds apparently so numerous when European explorers first arrived that “buzzard” (a colloquial name for hawks in Europe) came to define our bay on their maps.

I DISCOVERED Westport ospreys some 40 years ago — a lucky day for me. As a young Woods Hole grad student, from the other side of Buzzards Bay, I’d been looking for a nearby research project and knew about ospreys from studies elsewhere.

Westport River ospreys fit the bill, thanks mainly to a growing cluster of salt marsh nests on easily accessible and sturdy nest platforms, which local naturalists had built. And there was a welcoming community of volunteers who over the years had taken ownership of these birds, maintaining and monitoring their nests and helping them thrive.

My timing was lucky too. Along much of our Atlantic coast osprey numbers had crashed during the 1950s and 60s — the victims of insecticides in the environment, which killed eggs and even some adults. But by the late 1970s and early 80s, when I began my Westport studies, all that was changing. State and federal agencies had blocked use of the deadliest insecticides, so fish were cleaner and osprey eggs more viable. To my delight, I began to see nests packed with fledging young.

It was a heartening time to be studying ospreys. I witnessed the Westport nesting colony mushroom from fewer than a dozen pairs, most struggling to find nesting sites, to a vibrant colony of 60-70 nests a decade and a half later. Surrounding areas such as Martha’s Vineyard and coastal Rhode Island saw similar recovery, and my studies helped me understand the dynamics of this rapid growth — what made the difference between success and failure for a nesting pair. That was valuable information to share with colleagues across the US and globally, as ospreys in other regions also began to emerge from devastating losses.

IT’S TOUGH TO THINK of a more global bird than the osprey. Here in North America, you can find their nests from Florida to Alaska, and from Baja Mexico to Labrador. Spin the globe to Europe and Asia, and you’ll discover breeders scattered across northern latitudes from Scotland to Japan, as well as farther south in Australia and the Red Sea. Clearly an adaptable bird (only a handful of other wild birds have such a global range), there is one common denominator in their search for habitat because they live almost exclusively on live fish: water. Ospreys are never far from it, but those waters can vary greatly: fresh or salt; big or small; river, bay, lake, or ocean.

As with most wild birds, two things in particular spell the difference between nesting success and failure: adequate food and safe nesting sites. Ospreys are masters at finding fish, circling high to spot them and then diving fast and hard, with laser-accuracy, to snatch their slippery prey from surface waters. Big powerful feet and razor-sharp talons ensure that fish, once caught, don’t escape.

But not all waters hold fish, or at least those that ospreys can easily catch. Ospreys do best in areas where migratory fish swarm rivers and bays; big schools make for easy pickings. In Buzzards Bay, a small handful of fish appear in such pulses of abundance: herring and menhaden (aka, bunker or pogies). Many of Westport’s osprey nestlings are raised almost exclusively on these species — day after day, week after week. You have to wonder if they don’t get tired of a limited menu.

Good places to nest can be as tough to find as fish. A hundred years ago, our South Coast fish hawks nested mostly in dead trees near the shores of bays and rivers and the ocean. But as development and intensive farming eliminated many of those sites, ospreys shifted seamlessly to artificial structures, finding places to nest on power line poles, cell towers, and (over water) on dock pilings, channel markers, and buoys. And especially in our region, platforms built for ospreys on salt marshes proved to be favorites for these birds.

Historically, salt marshes were pretty much off limits to nesting ospreys. Flooded by storm tides, and prowled by wily predators like foxes and raccoons, marshes like those along the Westport River rarely attracted nesting ospreys. Not that some pairs didn’t try. Success in rescuing those nests, getting them off the ground and onto predator-proof structures, quickly transformed into a new community effort, one we might call “build it and they will come.” Platform-topped poles sprang up on Westport and other South Coast marshes, and proved to be magnets for nest-hungry ospreys. The era of the salt marsh “Osprey Garden” had arrived.

BUT GARDENS NEED TENDING, and so it was with these nesting colonies. Keeping the Westport platforms maintained (winter storms and ice often take a toll) has proven to be a challenge, but one ably met by local volunteers, increasingly under the guiding influence of Mass Audubon’s Allen’s Pond Sanctuary. Now the South Coast Osprey Project, this effort oversees more than 100 active nests and has become a model for osprey nest guardians elsewhere.

Some problems our osprey face are less easily solved. South Coast fish populations, especially those of the herring and menhaden that ospreys favor, are a tiny fraction of what they were historically. Over the years, industrial fisheries have taken an enormous toll. Balancing commercial fisheries with the needs of our coastal wildlife will be a challenge in the years ahead.

In addition, we have to remember that ospreys are “ours” only half the year. The other half (mid-September to mid-March) South Coast ospreys depend on Caribbean and South American waters, which come with hazards. Fish farming in particular is known to take a toll on these birds; thousands are shot each year at fish ponds in Brazil and Colombia alone. While progress has been made to curb this killing, much remains to be done.

Mining for gold and other precious metals increasingly poisons Amazonian rivers, prime wintering territory for South Coast ospreys and others nesting along the US Atlantic coast. We have little idea of what the impacts of these poisons really are, for ospreys or other wildlife, but reining in this abuse, particularly in remote lawless regions, is a challenge still in search of a solution.

But while there is plenty to worry about with our South Coast ospreys, there’s also plenty to celebrate. Nests fill up each spring with new eggs and young, the parents weathering extraordinary migrations to return to the nests that dot our landscapes. And new pairs arrive each year. Our osprey population, burgeoning with at least 200-300 nests, continues to grow, proving what wizards these birds are at finding new places to nest, and at discovering the best waters for fish.

If there’s one word that comes to mind when I think about our ospreys, it’s resilience. In their miraculous recovery from pesticides, their dedication to eggs and young, the vast distances they cover in migration with such routine ease, and their ability to adapt to a world we’ve changed so radically, ospreys inspire us. And it’s a good bet that, from Little Compton to Onset Bay, they will continue to do that in the years ahead.

Alan:

I live in Marion Massachusetts in the summers where we are surrounded by multiple Osprey nests. We have watched the local utility relocate several nests to luxurious custom built nesting poles along Point Road going towards Kittansett golf club. It is great to see the public utility support the growing osprey population.

In the winters, we live in Naples, Florida, where I fish on the intercoastal and see literally dozens of Osprey nest on the channel markers.

I am fortunate enough to play golf at an Audubon certified course called Hole In The Wall in Naples. Our wildlife committee and greens committee has erected several very fancy osprey poles along the water features of the course. One has attracted a nesting pair which have recently returned to start another generation. The other nest, which is located on one of our large water features with many fish has been vacant for four years. I would love some suggestions.

John Whittemore

Hi John, We’ve forwarded your comment along to Alan. Thanks for being a reader!