Cranberry farmers have always innovated throughout history, and our South Coast-based ones continue to do so in the face of climate change and competition from other regions in the country.

Cranberry farmers have always innovated throughout history, and our South Coast-based ones continue to do so in the face of climate change and competition from other regions in the country.

Please enjoy this reprint from our Holiday 2021 print issue. Written by Laura Killingbeck. Photography by Ann Mason.

There are very few farmers who would willingly flood their fields before harvest, but cranberry farmers are a special bunch.

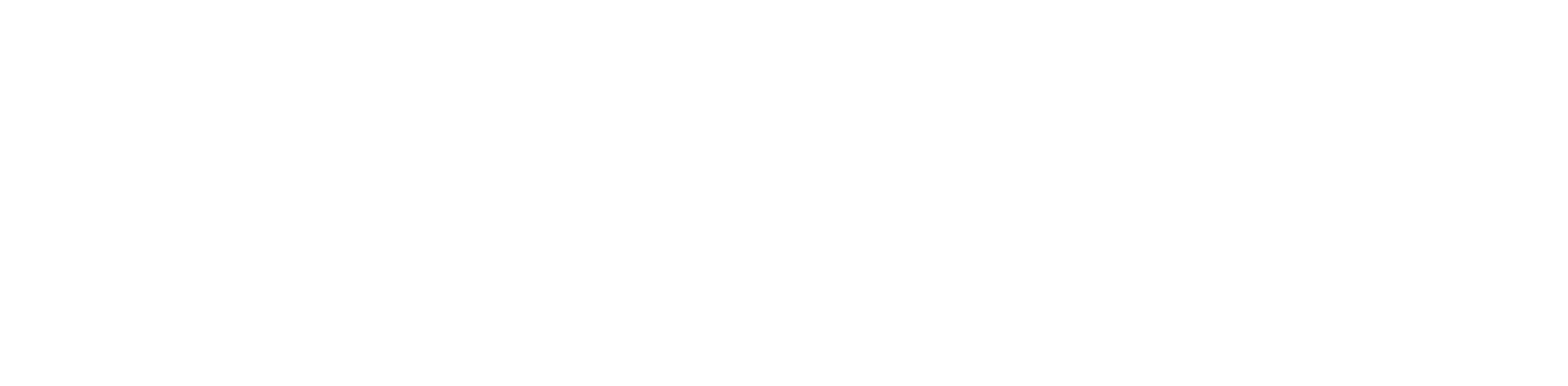

Each fall, many of them fill their dry bogs with water, dislodge the fruits with a machine called a reel, and watch the red berries rise to the surface. (Some farmers do a dry harvest.) Once the berries are afloat, workers use rakes to corral them like sheep in a floating fence called a boom. Then, a large tube vacuums the fruits out of the boom into a nearby sorting station. From there, the berries are loaded into trucks and sent off to be squashed into juice and sauces. This process is the result of hundreds of years of industry innovation. It also marks a moment in time that is quickly changing.

Massachusetts has more 14,000 acres of cultivated cranberry bogs and is the second biggest growing region in the world. The South Coast is home to small, diversified farms with several acres of bogs, as well as larger cranberry operations with thousands of acres.Each fall, these bright, crimson-covered bogs form an iconic part of the local landscape.

Massachusetts has more 14,000 acres of cultivated cranberry bogs and is the second biggest growing region in the world. The South Coast is home to small, diversified farms with several acres of bogs, as well as larger cranberry operations with thousands of acres.Each fall, these bright, crimson-covered bogs form an iconic part of the local landscape.

Innovation has always been part of New England’s cranberry industry. In the early 1800s in Dennis, a man named Henry Hall noticed that cranberries grew better when beach sand blew over them. He transplanted some vines, fenced them in, and covered them with sand. This technique was so successful that he started shipping barrels of berries to Boston and New York.

Hall’s early plant domestication and entrepreneurship was the precursor to the next two hundred years of cranberry farming; it also set in motion a global industry that’s now valued at nearly 300 million dollars. In order to stay competitive, modern cranberry farmers must continue to innovate and adapt to new challenges.

Hall’s early plant domestication and entrepreneurship was the precursor to the next two hundred years of cranberry farming; it also set in motion a global industry that’s now valued at nearly 300 million dollars. In order to stay competitive, modern cranberry farmers must continue to innovate and adapt to new challenges.

“I’m in my forties, and growing up it was like, ‘oh, someday climate change could happen if we don’t act.’ But the reality is, it’s happening now. We can see it and we can feel it,” says Katherine Ghantous, a scientist at the UMass Cranberry Station, an outreach and research center in East Wareham that works to enhance the economic viability of cranberries in Massachusetts. They manage eleven acres of bogs, conduct research, and provide outreach to growers. “We have an open-door policy, so we have growers walking up and down the halls with clumps of weeds, and bags of bugs, and rotten fruit. They know they can show up and talk to us and we’ll help with diagnostics and things like that.”

According to Ghantous, growers are seeing shifts in temperature that impact cultivation strategies. Every three to five years, growers normally flood their bogs in the winter and let the water freeze. Then they drive buggies over the bog ice and spread sand on top. When the ice melts in the spring, the sand settles over the plants.

According to Ghantous, growers are seeing shifts in temperature that impact cultivation strategies. Every three to five years, growers normally flood their bogs in the winter and let the water freeze. Then they drive buggies over the bog ice and spread sand on top. When the ice melts in the spring, the sand settles over the plants.

But recent shifts in temperature have changed that. “I can’t tell you the last year there was good ice for sanding,” says Ghantous. “It’s a very obvious change.” Temperature changes also affect harvest times and pest pressure. Unpredictable conditions wreak havoc on seasonal planning.

“We’re seeing more extreme climactic events in terms of drought, and an excess of rain and storms,” says Parker Mauck, the Director of Grower Relations and Corporate Procurement at Decas Cranberries. “But these cranberry growers are incredibly innovative.” He described how one farmer started using construction equipment to fling sand over the bogs when the water didn’t freeze. “Cranberry growers make their own equipment. If they need something, they build it.”

“We’re seeing more extreme climactic events in terms of drought, and an excess of rain and storms,” says Parker Mauck, the Director of Grower Relations and Corporate Procurement at Decas Cranberries. “But these cranberry growers are incredibly innovative.” He described how one farmer started using construction equipment to fling sand over the bogs when the water didn’t freeze. “Cranberry growers make their own equipment. If they need something, they build it.”

Growers are also adapting to climate change by using technology to monitor conditions on the farm. They hope this precision will help identify increasingly narrow windows of opportunity that might no longer be discernible to human judgment. Drones and automation now supplement farmers’ decision-making on key factors in cultivation.

Some growers are also diversifying their farms with renewable energy. Keith Mann, a grower in Buzzards Bay and a board member of the Cape Cod Cranberry Association, added wind turbines and solar panels to his farm. The turbines provide electricity to five different school districts and five different municipalities, as well as give the farm a new revenue stream.The solar panels power the rest of the farm.

Cranberries are perennial plants with a very rare quality: they can live indefinitely. Many farms still have heirloom varieties, and some vines have been in production for over a hundred years. A lot of local growers are multi-generational families who’ve been farming the same plants for decades.

Cranberries are perennial plants with a very rare quality: they can live indefinitely. Many farms still have heirloom varieties, and some vines have been in production for over a hundred years. A lot of local growers are multi-generational families who’ve been farming the same plants for decades.

But like most large-scale agriculture, cranberry growers are tied to a market that demands the impossible: infinite growth.Heirloom varieties that continue to thrive on local farms are becoming less and less viable in the commodity market. The effects of climate change are challenging, but for South Coast growers there’s another reason it’s so hard to stay afloat: the industry itself.

In the early 1970s, Massachusetts’ cranberry growers averaged just over 90 barrels per acre. Innovations in tools and management led to increases in productivity, and by 2015, the average yield had nearly doubled. But in recent years, growing regions like Wisconsin and New Jersey have surpassed those numbers by developing even higher-yielding hybrids. These new plants have the potential to produce three times as much fruit per acre as native varieties. Now, if South Coast growers want to compete in the global market, they’ll need to replace their heirloom vines with new hybrids. This difficult process is called bog renovation, and can cost up to $40,000 an acre.

In the early 1970s, Massachusetts’ cranberry growers averaged just over 90 barrels per acre. Innovations in tools and management led to increases in productivity, and by 2015, the average yield had nearly doubled. But in recent years, growing regions like Wisconsin and New Jersey have surpassed those numbers by developing even higher-yielding hybrids. These new plants have the potential to produce three times as much fruit per acre as native varieties. Now, if South Coast growers want to compete in the global market, they’ll need to replace their heirloom vines with new hybrids. This difficult process is called bog renovation, and can cost up to $40,000 an acre.

“It’s a massive investment,” says Ghantous. “And once you’ve planted the new variety, it’s maybe three to five years before you get a full crop. It’s the long game for these guys. In order to even try to make a living, you have to grow more and more and more.”

When I ask what she’d like to tell South Coast consumers, she laughs. “They should buy more cranberries!” she says. “It’s such a cool part of Massachusetts history. We have some farmers that are seventh generation on the same land. Cranberries are in their blood.”

She also recommends that people visit a cranberry bog and see the harvest for themselves. “I’ve been working in cranberries for over 15 years and every harvest is still as exciting to watch,” she says. "It's beautiful."

To find a cranberry bog tour near you, visit cranberries.org

Thanks for visiting South Coast Almanac! Please consider supporting our mission to bring you the stories of the people and places of the South Coast by becoming a subscriber to our print magazine. Just $19.99 a year brings you the best of the South Coast.

Thanks for visiting South Coast Almanac! Please consider supporting our mission to bring you the stories of the people and places of the South Coast by becoming a subscriber to our print magazine. Just $19.99 a year brings you the best of the South Coast.