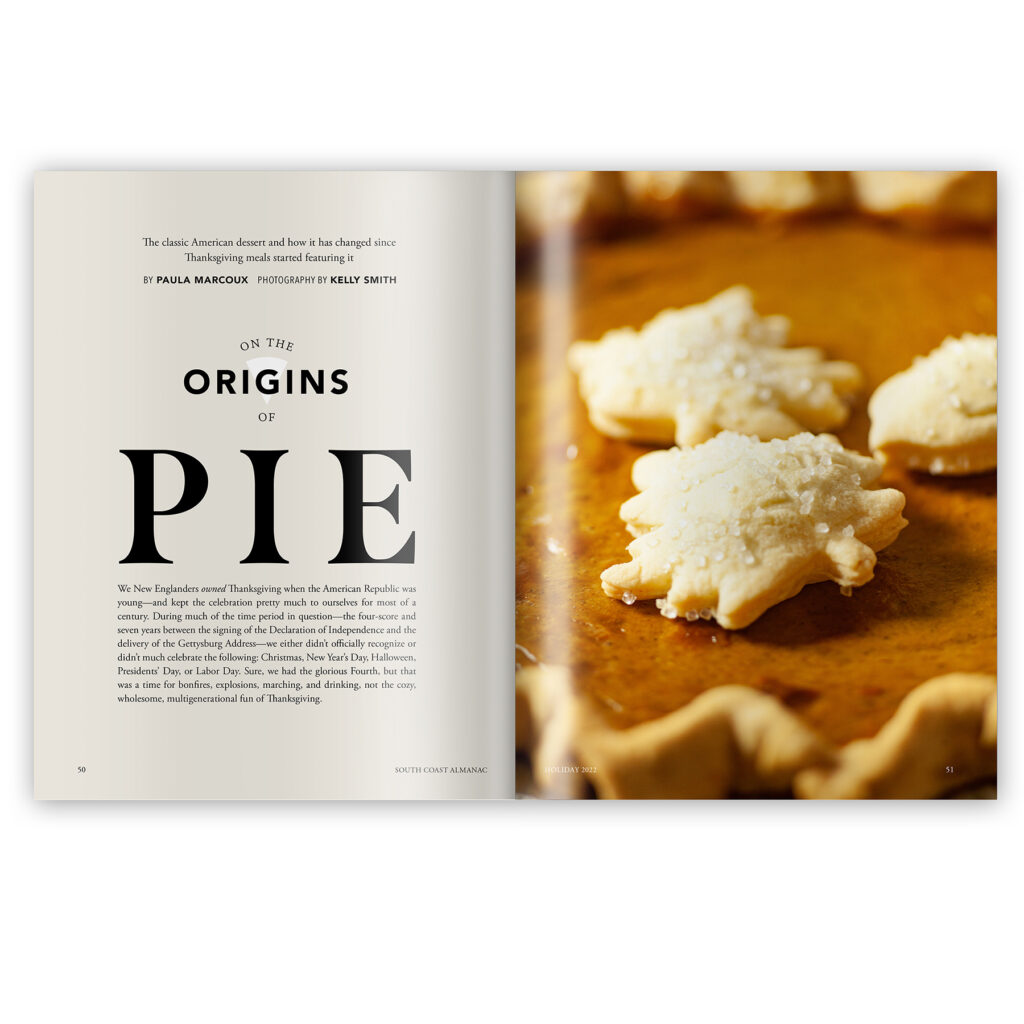

The classic American dessert and how it has changed since Thanksgiving meals started featuring it.

By Paula Marcoux Photography by Kelly Smith

We New Englanders owned Thanksgiving when the American Republic was young—and kept the celebration pretty much to ourselves for most of a century. During much of the time period in question—the four-score and seven years between the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the delivery of the Gettysburg Address—we either didn’t officially recognize or didn’t much celebrate the following: Christmas, New Year’s Day, Halloween, Presidents’ Day, or Labor Day. Sure, we had the glorious Fourth, but that was a time for bonfires, explosions, marching, and drinking, not the cozy, wholesome, multigenerational fun of Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving was the time for homecomings and generosity, and for the open expression of gratitude for family, community, good luck, and bounty. It was celebrated largely by cooking, baking, and eating, and some of the foods people chose to eat on the holiday during this period became cemented into the American tradition as iconic Thanksgiving dishes. This has been admittedly a mixed blessing, but fortunately for posterity one of nineteenth-century New Englanders’ most-loved foods was the pie.

Frequently-mentioned Thanksgiving pies from those years include apple, pumpkin, and mincemeat, all familiar to us now, but generally then made with a lot more variations than have come down to us in our more rigid-thinking era. A secret benefit of my many years of research in archival recipe collections and manuscript cookbooks has been my exposure to these unorthodox ideas. Thanks to past generations of Southeastern Massachusetts cooks, my recipe box includes a robust sliced apple pie seasoned with molasses, a delicate squash custard pie flavored with lemon rind rather than today’s obligatory spices, and a tasty but heart-stopping mince pie filled with tender beef tongue, nutmeg, cider, chopped apples, brandy and suet. And then there are those mouth-watering “plain” tarts made with cranberries or huckleberries—just fruit and sugar baked on buttery pastry—direct and delicious.

One last special antique pie category—of which pumpkin pie is the most obvious survivor today—comprised a spectrum of rich sweet custard pies based on pureed fruit or vegetables like potatoes or carrots, flavored with sherry or brandy, nutmeg, rosewater and currants. These plush-textured gems were Thanksgiving pies par excellence, and an abiding mystery of New England foodways is why they ever vanished from our culinary inheritance.

One of my favorite “disappeared” pies of the period had several names, including Marlboro Pudding or Marlborough Pie, or Lemon Apple Pie. Here’s a version, called Apple Pudding, from the lovely and quirky manuscript notebook that Emma Cornelia Ricketson of New Bedford started in 1862:

“Apple Pudding. Mrs. Russell. Stew & strain 10 apples – add 6 spoons melted butter – 6 eggs – juice & peel of 1 lemon – sugar to taste – bake in paste without covering.”

Maybe you’re wondering what makes me think that this is a pie, and not a pudding, as the title indicates. Two things make me sure. First, for the couple centuries preceding Emma’s setting pen to paper to record this recipe from Mrs. Russell, the term pudding indicated a head-spinning spectrum of dishes throughout the English-speaking world. The delightful category of pudding pertinent here was a sweet custardy fruit or vegetable compound baked with an undercrust, like the pumpkin pie we know well. Calling the dessert in question an apple pudding would distinguish it from an apple pie made with sliced apples, also hugely loved for centuries. (Oh, and yes, there was also a pumpkin pie made from sliced pumpkin called, yes, pumpkin pie, forcing the name pumpkin pudding on the other type sometimes…) This usage was changing in Emma Ricketson’s day, so it’s charming to see her going old-school with her nomenclature.

The clincher, though, is that she outright tells us to “bake in paste without covering,” i.e., bake it with an undercrust. In fact, as you can see, it’s pretty much the only instruction she gives us.

Other versions of Marlboro Pie from our region use cream, sherry, nutmeg, or rosewater, and are also good in their own way; one from Plymouth starts with raw grated apple, and is also wonderful. But this recipe delivers a purity of flavor that would be quite bracing following the confusion of the Thanksgiving food-rush—or better yet, saved for a solo performance after the diner’s recovery.

This year, as the weather cools and the days shorten and you think about your Thanksgiving table, spare a thought for those South Coast cooks of old taking stock of their larders and prepping for the big holiday. With their farms and barnyards on the verge of falling into winter dormancy after months of labor, they must have delighted to showcase the season’s harvest in a staggering array of pies. But their satisfaction had to have been tempered, at least a little, by the willful profligacy of blowing through so much of the last supply of eggs, cream and milk they would have until the cows and hens came back online in spring. Ah, but when you only have that one holiday, you really have to make the most of it!

Here’s how to make an old-fashioned apple custard or Marlboro pie.

Emma Ricketson’s recipe works out to fill a 9-inch pie pan or

an 11-inch tart pan, lined with your favorite flaky pastry.

6 eggs

6 ounces (1 cup, plus 1 tablespoon) granulated sugar

6 large apples, stewed and strained, or 1 cup fresh,

tart applesauce

A lemon, zested and juiced

6 ounces butter, melted

A 9-inch unbaked pastry shell

- Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

- Whisk the eggs until frothy, then whisk in all the other filling ingredients. Pour into the pastry shell.

- Bake for 45-50 minutes, depending on your pan choice and oven. The pie should be just set up—with a little jiggle remaining in the center—and pale golden brown. (If you look at it after 30 minutes, and the top is already beginning to brown, turn the oven down to 325 degrees for the remainder of the time.)

- Cool on a rack and serve warm or cool. Serves 8-10.

Here’s how to have someone else make you an old-fashioned pie.

Not inclined to bake, yet eager to eat one of those old-fashioned pies as part of your celebration? A couple of South Coast pie-bakers are known for producing traditional custard-type pies using locally-grown fruits and vegetables. Both of them make their own pastry, source their filling ingredients locally, and take pride in producing scads of delicious pies, by hand and from scratch.

It’s fair to say that Wilma Bruining of Wilma’s Kitchen in Little Compton (www.sakonnetevents.com) is a true pumpkin whisperer. She selects her pie pumpkins, including a very special heirloom called Long Island Cheese, from Old Stone Orchard and Wishing Stone Farm, both in Little Compton. After whacking the pumpkins up and seeding them, she oven-roasts the flesh, then chills it for several days, weighted, to refine its texture and reduce its moisture. She purees the resulting quintessence of pumpkin, tempering it with half-and-half, eggs, sugar, and spices, before baking it in pastry shells.

Demand for pumpkin pies is of course at a peak at Thanksgiving, but Wilma always freezes some of her prepared pumpkin for the true aficionados (like this author) who look for pumpkin pies into the winter.

I asked Meredith Rousseau, of Artisan Bake Shop in Rochester (www.artisanbakeshop.com), how old-school custard pies could possibly compete with flashy, uptown, fillings in her repertoire, like double-chocolate-pecan. “Our old-fashioned New England pies have gained popularity over the years as word of mouth sparks the interest of folks in the area,” she replied. “We also find that our pies have become a holiday tradition in many families. The custard pies are especially nostalgic for our clients and for me. The greatest compliment we receive is to hear that our crust and filling bring back childhood memories of homemade pies.”

We post past articles on our website regularly. If you would like to get the magazine, go here to subscribe.